Accents and register

How to be a Brit

The Hungarian journalist and BBC reporter, George (György) Mikes – pronounced / ɱ ‘i: ke ʃ / – commented wryly in his book “How To Be An Alien“ (1946), a classic of “British humour”, when – as a foreigner in England – he realised the importance of having a “suitable” accent:

“My dear, you really speak a most wonderful accent, without the slightest English!”

Accents are of course connected to our origins and culture. There are national, regional and individual accents and these can link a person to social class, educational background, and character.

Who am I?

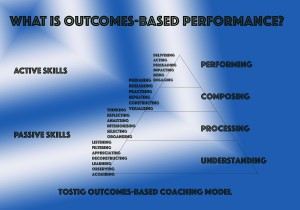

As many academics have shown over many years, the whole concept of one’s identity as a person cannot be separated from language. Languages express emotions, facts, notions of time, space and morality, in different ways, and arise as the communication surface structure built on generations of history, tradition, law, belief and education. How we perform depends on first how we understand, process and compose language.

Outcomes-based coaching and learning

There is the larger question of how English, as an international language, can serve to perform acts of identity that are specific to one’s own language. As linguists have tried to show, all languages share some deeper, innate, structure or else how could the same human being, theoretically, be born anywhere on the planet?

Mikes started his famous book with the words “In England, everything is the other way round”.

Culture itself cannot be entirely systematised, despite the efforts of anthropologists, psychologists and sociologists. Along with dress and other customs and habits, language is the outside sign of what a person deems themself to be. Actors, who play the part of another culturally different person, in the theatre, see this very clearly.

Consequently, as soon as we open our mouth, we “give away” something about who we are and how we wish to be perceived by others. The process of “acculturation” – the process of internalising the implied rules of a “discourse community” – is something that anyone who lives or works with other language groups or nations, understands from day one. Culture “shock” can be one outcome of this difficult process. Bridging differences effectively, means using language very skilfully and being sensitive to culture.

Isn’t it?

For the learner of a second language, there results from this the thorny question of how to “sound right“. In some ways this leaves one free to choose the model one prefers, to “sound” correct in whatever circles that person happens to frequent.

It’s quite well-known that the use of question “tags” is a feature of spoken English:

“It’s a lovely day, today, isn’t it?”

“Oh yes, they said it was going to rain, didn’t they.”

“It’s so nice when it’s hot, isn’t it.”

“Yes I love it, don’t you?”

As George Mikes observed, “In England, you must never contradict anybody when discussing the weather.”

Similarly, the words Yes and No – straightforward as these may seem – are loaded with difficulty, and cultural overtones, when we say “Yes” but mean “Maybe”; or when we say “No, I don’t mind at all” – and mean “That’s absolutely fine!”

In addition to the vexed question of “British understatement”, there is the related issue of the “proxemics” of a given culture and the register of particular words and phrases. How should we “act”? How close should we stand to another person? How soon is it appropriate to ask a personal question? How direct or indirect is it appropriate to be? The exact combination of phonetic training, listening to sounds, using the voice and breathing in order to “come across” with confidence and fluency, is something that requires a thorough analysis and discussion.

Contact us to find out more!