Manage your words well

Using English well in an international context is as important for native speakers of the language as it is for non-native students and other international users of English.

Whether this is because English happens to be the lingua franca of the organisation, company, corporation or community, or because those involved in any meeting have chosen to use English themselves, there is every chance that there will be people with differing ranges of experience and ability in the language, just as this would also be the case with people speaking French, Hungarian, Russian, Spanish, Mandarin, Turkish, Arabic, Swahili or Gaelic!

Who of us can say we would be confident to attempt to do all that we do in our own language in any other language? We can perhaps learn how to order a prawn sandwich or a taxi, or to greet someone at the airport, wish them a good journey or thank them for their help. This does not take long and is a sensitive and polite thing to do when doing business with others. It shows that we have made a little effort to learn about their ways.

Just as we can learn a few words, we can also learn about the cultures we interact with.

This process works both ways, because – though there is common ground within cultures for anything that we may need to discuss, and certainly room for exploration in a number of areas (or business would never happen or have been going on for thousands of years!) – there are also certain highly sensitive areas of “sacred ground” where discussion may be very difficult or even impossible.

Encroaching on these sensitive spots is risky and potentially rude. This is as true of the English-speaking culture as it is of any other.

The things that affect our identity are hard to define and having a well-researched book to refer to is essential; I recommend Richard Lewis’ excellent work for a clear and intelligent model when entering new ground in any culture.

Where the deeply-embedded elements of a culture’s specific core value system and the individual’s own modus operandi can have multiple layers that are not open to scrutiny, the language itself can give us the clues we need to how a people think.

We should take care with our words whether with other native speakers or with non-native speakers.

The Ratners Jewellery store in Regent Street, London, part of the chain owned by Gerald Ratner, which made a 112 million profit in 1990.

Careless language can be very costly.

A famous story is that of successful businessman Gerald Ratner who in 1991 wiped £500m off his share value with one speech, when talking of his own high-street jewellery, he inadvisedly announced it was “cheaper than an M&S prawn sandwich and probably wouldn’t last as long”.

Another story is that of the Topman clothing chain and the firm’s brand director, David Shepherd, asked in an interview in 2001 to clarify the target market for his clothes, he replied: “Hooligans or whatever.” He went on: “Very few of our customers have to wear suits for work. They’ll be for his first interview or first court case.”

The company later suggested that the word “hooligan” would not be seen as an insult among its customers.

Such careless words may seem amusing or tough but they have consequences. In 2006, John Pluthero, the UK chairman of Cable & Wireless, sent a memo to staff, which said: “Congratulations, we work for an underperforming business in a crappy industry and it’s going to be hell for the next 12 months.” He warned of job losses and added: “If you are worried that it all sounds very hard, it’s time for you to step off the bus.” Many did just that and found work elsewhere.

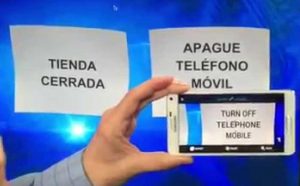

Another pitfall is translation and translation devices. They are not capable of understanding cultural and linguistic nuance. The ambiguity of translation is well summed-up with the example of a biblical quote, meant to express the struggle facing the industry at that time and to motivate the employees to make an extra effort, and that was used in an after-dinner speech translated into German

“The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak”.

This came out as “The schnapps is strong but the meat is rotten”

Language is not a set of conditioned responses triggered by previous words, because we can change these patterns at will. This allows us creativity and individualism. Chomsky’s “poverty of the input” hypothesis tells us that what a child can produce in language is MORE than the input they have received via their parents or peers. This “new potential language” has come from within the child as he/she has acquired the deeper syntax. Somehow, the child knows that the structure “Daddy what did you bring that book that I don’t want to be read to out of, up for?” is the only right use of syntax for English, for this question.

Pace is a deciding factor. People are more inclined to get excited and emotional speaking their own language than speaking English, this is hard to lose in a foreign language, suggesting that the control of output and having to pace themselves, will affect themselves and others

Impact

There are several negative and positive associations: native speakers are imagined to have more sensitivity but often they have less. Consequently natives can benefit from observing how a non-native speaks, or try to compose themselves in FL to see how it feels.

Having a slower pace enables better listening and more self-composure. However the emotions inside the L2 speaker are likely to be very high and for the L1 speaker, having to modify their language to obtain better results may at times feel frustrating, too.

At P.i.E. we can help you develop sensitivity to language that leads you to better outcomes. As a non-native we can show you how English works and how to use it effectively, in your own specific situation, according to different scenarios and your personal choices, understanding norms and idiosyncrasies.

Equally important, as a native speaker we can show you how good language management will lead you to better relationships, deeper awareness of communication and the avoidance of costly mistakes, and to a level of self-composure that is not over-confident but mature and manifested in a spirit of mutual respect.