Managing your Language for better Embodied Results, York International Coaching Week

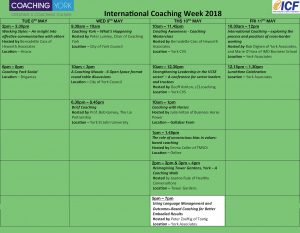

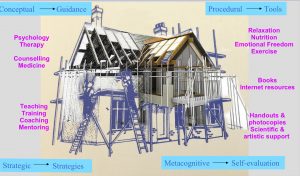

In May 2018 I was proud to be involved in the York International Coaching week.  I spoke* at Peasholme House, the home of – and courtesy of Bob Dignen, Director of – York Associates. The ICW (full listings below**) is organised by Mr Peter Lumley, Chartered Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), and whose tireless work with Coaching York is putting this beautiful city well and truly on the map where coaching is concerned. *My workshop explored the importance of language mastery, and the cross-overs between language coaching and awareness, with topic/problem-based or situational-based coaching and mentoring, around personal and company goals and culture. It covered how more effectively to understand one’s physical response to a range of scenarios and thence embody purposeful and harmonious behaviour that is also conveyed in language. It thus focuses on how we understand and perform. There was also some analysis of personal and corporate “culture” as well as of the theory of chao-dynamics, looking at how outcomes emerge by dint of the mastery of language and the skilful ways in which communication is embodied. Please email me via info@tostig.co.uk There is a question in the back of my mind, preparing this, namely, what makes us want to listen and want to be involved; why do we sometimes “switch off” and why, at others, sit up in readiness? Embodied leadership states and how to access them, is a perennial aim for organisations wanting to avoid costly mistakes and get the best possible outcomes.

I spoke* at Peasholme House, the home of – and courtesy of Bob Dignen, Director of – York Associates. The ICW (full listings below**) is organised by Mr Peter Lumley, Chartered Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD), and whose tireless work with Coaching York is putting this beautiful city well and truly on the map where coaching is concerned. *My workshop explored the importance of language mastery, and the cross-overs between language coaching and awareness, with topic/problem-based or situational-based coaching and mentoring, around personal and company goals and culture. It covered how more effectively to understand one’s physical response to a range of scenarios and thence embody purposeful and harmonious behaviour that is also conveyed in language. It thus focuses on how we understand and perform. There was also some analysis of personal and corporate “culture” as well as of the theory of chao-dynamics, looking at how outcomes emerge by dint of the mastery of language and the skilful ways in which communication is embodied. Please email me via info@tostig.co.uk There is a question in the back of my mind, preparing this, namely, what makes us want to listen and want to be involved; why do we sometimes “switch off” and why, at others, sit up in readiness? Embodied leadership states and how to access them, is a perennial aim for organisations wanting to avoid costly mistakes and get the best possible outcomes.

What would inspire me?

We confront the inevitable paradox: people are in positions who are in reality doing the opposite of what they are meant to do, or say that they are doing. The question arises, is this by mistake, by design, does it perhaps emerge from a sense of confusion? Is there even a perceived destabilisation culture, where we find ourselves having no other option, trapped, playing a role, wearing a mask that doesn’t fit too well?…. Consumer Strategic Insights (CSI) Director Jorge Rubio’s ‘Brain Spa’ was a kind of “creative space” designed to allow its participants to”set themselves free” of the numerous affective filters that prevent us from – as Jack Welsh was forever asking us to do – “reaching our full potential”, and removing barriers within the meritocracy.

How does this make you feel?

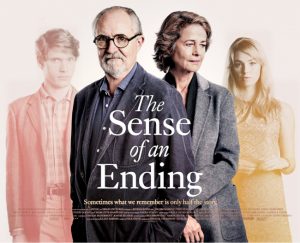

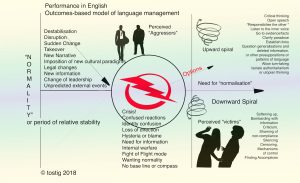

Language management, dealing with destabilisation in particular, is a way of delivering clear outcomes-based learning, incorporating a creative emergence of solutions at the same time. Outcomes-based notions are programmed into us from an early age; suffice it to say that the idea is pre-programmed into most children, as they grow up understanding that they need to learn (and often only learn) what is “in the test”. Cramming what I need to know “to get the answer right” is present in schooling and culture. It is there in the idea of the happy ending, of the end justifying the means, the ever-present teliological story format, the Tick-Tock that famously Professor Sir Frank Kermode referred to in his book, “The Sense of an Ending”. We live – according to this great critic – “In the Middest” and, this “Middle Time” – the age in which we now live – is characterised by a sense of permanent change, where what was “good” has declined and is in need of renovation. A process of painful purging needs to be undergone, which allows us to explain the chaos and ‘crisis’ we see unfolding around us. (Has some ancient trauma led to a state of amnesia in our deep collective unconscious perhaps re-emerging at troubling moments that we struggle to comprehend?)

A recent film based around Julian Barnes’ reading of Professor Kermode’s theory

I read Kermode’s work when preparing my thesis in 1980 on Racine’s “Phèdre” and the idea that we already think we know the “ending” before it happens. Accordingly, in education, as in life and fiction, we feel the need to evaluate and be evaluated according to the “backwash” of expectancy, from the presupposed best or expected outcome – whether imposed by the parents, religion, traditions, the school system and its preparation for a career, or in work, the perceived company culture. Outcomes-based learning is a theory developed by John Biggs, using “constructive alignment”: we start with the outcomes we intend students to learn, and align teaching and assessment to those outcomes. Managerialism is explicitly eschewed within this theory, however.

How though, do we promote creativity, if participants believe there is a fixed outcome to be reached? As I shall outline in my talk, the way to bring about the emergence of creative solutions lies in how language is managed and in how we embody the process of change. Unfamiliar to many will be the work of Iyla Prigogine and Chaodynamics – that change is everywhere and in everything, that language is an attempt to make sense of natural state of flux, and culture is a way to fix and control or standardise the inevitable sense of destabilisation that comes from change. I have worked with this previously for many years and know it from political mechanisms of change as seen also in the works of Marcuse and Gramschi (I am not a proponent of these ideas) as well as in NLP.

Viscount Ilya Romanovich Prigogine 25 January 1917 – 28 May 2003) a Belgian physical chemist and Nobel Laureate

As Frank Kermode also pointed out, what happens is irreversible because of the inevitability of the ticking clock of time, and that what is said cannot be unsaid; actions, when carried through, are complete. A view of human interaction is also developed from the work of Ilya Prigogine, noted for his work on dissipative structures, complex systems and irreversibility.

Managing one’s language implies a use of language to oppose the natural tendency to dissipation and destabilisation in complex systems, a kind of NLP for empowering – and to de-programme the mind and set it free. Prigogine developed the concept – at the University of Austin in Texas – of “dissipative structures” to describe the coherent space-time structures that form in open systems in which an exchange of matter and energy occurs between a system and its environment. This led to the theory of Chaodynamics and the idea of what he called a “concentric” approach to nature/communication to reestablish order after a major disruption. A good illustration of this can be found in theories of cultural change, and also, more negatively, as it is used in psychological warfare and in subversion tactics. In a demotivation stage, people worryingly and understandably feel bombarded with information and criticism, this leads to identity loss, and sometimes deliberately to the shaming of non-compliance. Acts or words that are violent or introduce sudden changes are used, silencing and censoring, and – in the most negative scenarios – setting up mechanisms of control through trusted accomplices and so-called useful idiots, or a sense of “us and them”. The coach’s work begins here to reverse this and re-establish truth and objectivity, establishing the principles of free speech and trust. Using language skilfully, the good leader or manager manages to bridge differences and overcome agitation from within, where the sense of disempowerment and imposition of a new narrative is often felt as being disenfranchising and as a real physical problem.

During a period of intense crisis, confused reactions and more identity confusion, loss of direction, even hysteria or blame are felt as a kind of internal warfare. The coach here listens and acts to encourage a clear and responsible use of words. By clarifying paradoxes, generalisations and unspecified references, deleted information, universals, or other presuppositions or patterns of language, that we note in NLP, we can bring about a creative outcome that is desired but not known or imposed from the outset.

How, if a person is feeling intense demoralisation, can there be a change towards an empowered use of language that is at the same time elegant, powerful and poised? How do we bring gracefulness into an obviously stagnant sense of discomfort, or damaged stalemate?

In what might be considered a “normalisation” phase, the coach or other responsible actor – whatever their position – has a difficult task in liberating one who is at a stalemate or downward spiral, and challenging those who are perceived as aggressors, to reform their patterns of behaviour via critical thinking, open speech and by opposing authoritarianism or utopian thinking. So, looking at the “positive” side to this…. The coach works with perceptions in language with those perceived to have caused a de-stabilisation and and in order to establish facts in a neutral way and restore grace, poise and meaning to what is otherwise seen as desperate. This is then embodied in a physical way, turning defeat into victory and bringing about healthier, more mutually-beneficial outcomes.

** For the full listings and details please read here: ICW Events Listings2018 (1)